|

| A Gaggle of Hats |

There is no more iconic symbol and image of the eighteenth century than the three-cornered, or Tricorne, hat. Americans imagine their founding fathers wearing such hats, it is the hat of Frederick and Catherine the Great, George II and III; it is the hat worn in the art of William Hogarth and David Morier. Today, the image of people wearing tricorne hats is utilized by historic sites, media companies, and football teams.

|

| Detail of a portrait of Frederick II of Hesse-Cassel, (DHM) |

|

| George II by artist David Morier |

1) The term "tricone hat" was not used in the eighteenth century.

The earliest English language usage of the term tricorne hat (and I am open to correction if you can date it earlier) appears to be in the mid-nineteenth century, with many examples from the 1860s and 1870s. In French and German, the term appears as early as the 1830s.[1] So, if people living in the eighteenth century did not call these hats, "tricorne hats" what did they call them?

|

| P. J. de Loutherbourg simply used the term "hat" to describe this headgear |

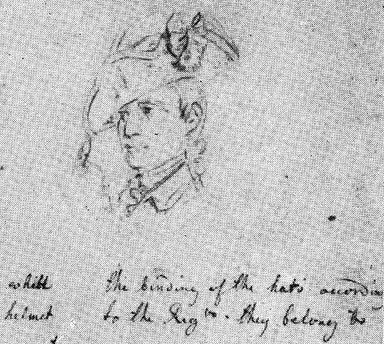

The eighteenth-century three-cornered hat, the "cocked hat", was ubiquitous across Europe. Perhaps not surprisingly, many contemporaries simply called this design a "hat", as it was the most common form of male headwear across much of the eighteenth century. Where more specialized terms existed, they usually described specific hat designs.

Englishmen occasionally used the term, "three-cornered" when describing their hats in contrast to the hats of other cultures, but did not use the term tricorne.[2] Perhaps surprisingly to us, they used the term "three-cornered cap" more frequently than hat. By the end of the eighteenth century, the term, "three cornered hat" became more common, as contemporaries tried to distinguish this garment from other emerging sorts of headwear.[3]

|

| British Military-Style Cocked Hat, 1750s (M. Brenkle) |

2) The modern term "tricorne hat" brings together a group of hats which contemporaries often viewed as distinct.

|

| Reproduced Hat of the 8th Regiment of Foot (M. Brenkle) This hat appears to be tending towards the Ramilies/l'androsmane style |

|

| A variety of hats are on display in the Voelkertaefel, from left: French, Italian, German, English, and Swedish |

3) The term "tricorne" is used as shorthand for hats between 1700 and 1800, making the eighteenth-century appear static and monolithic to the general public.

Much of the specialized language for cocked hats before 1780 was designed to differentiate various unique styles and cocks. Only at the end of the eighteenth century did the critics of tricorne hats begin to represent them as monolithic and similar. As it was a symbol of wealth and good standing, the popular mood began to turn against the three-cornered hat in the 1790s. An anonymous author wrote the following in The New-York Weekly Magazine:

Among the many things invented by man for his use, none perhaps is more ridiculous than the three-cornered hat at present used by some persons. That it affords but an inconsiderable shelter to the head, is a truth scarcely to be denied; and that the face of him who wears it remains exposed to the piercing rays of the sun, is equally true. If our ancestors deemed it a conveniency to wear the hats in question, experience teaches us at the present day, their great inutility: And shall we then willing smile on those customs which (tho' formerly practiced) proves at present highly injurious? No; Let us cosult our own feelings, and not the habits of former times.-- Common sense points out their inconsistency, and reason mocks the stupidity of him who madly submits to be ruled by custom, that tyrant of the human mind, to whose government three-fourths of this creation foolishly subscribe their assent. Again, the weight which is comprised in a hat of that size, is a sufficient argument for their abolition. Wherein then can the utility of such an unwieldy machine consist? Is not the round hat more becoming? And does it not finally prove to the head by far the best covering? The contrary cannot be urged unless through prejudice or selfishness. That it looks respectable and sacred, may be urged in favour of it; to this I reply, that if to be impudent constitutes either of those characters, the three cornered hat has the great good fortune to be superior to the other. It may be further advanced in its favour, that by letting down its brings it will answer the purpose of an umbrella in a hot summer day: ture that for size it may, but where is the person that would not rather make use of the real than the fictitious machine? Why was the pains taken for the invention of an umbrella, if the hat could be made to answer the same views? Was it not because the hat attracting the rays of the sun, was found to be injurious to the eyes, and therefore recourse was had to a machine which proved not only shelter from the sun, but to the eyes far more beneficial. To conclude, nothing but a false pride, and a desire to be conspicuous, could ever induce a person thus inconsistently to use that which will finally prove his folly. -- TRYUNCULUS, New-York, July 7, 1796.[10]Just as the revolutionaries toppled the monarchies of Europe, the great push to end social deference finally destroyed the three-cornered hat.

|

| recreated American cocked hats |

The cocked hat is an iconic symbol of a fascinating historical era. Regardless of what you choose to call this hat, I hope this post has providing some thoughts on the precision of language when it comes to historical objects, and how terms which are completely ubiquitous today may not reflect the terminology contemporaries used to describe these objects.

If you enjoyed this post, or any of our other posts, please consider liking us on facebook, or following us on twitter. Consider checking out our exclusive content on Patreon. Finally, we are dedicated to keeping Kabinettskriege ad-free. In order to assist with this, please consider supporting us via the donate button in the upper right-hand corner of the page. As always:

Thanks for Reading,

Alex Burns

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Anon, Archives historiques et littéraires du Nord de la France (Vol III, 1833) 45. Anon, Das Ausland: Eine Wochenschrift für Kunde, (Vol 6, 1833), 965.

[2]See, Mortimer Harley, The Harleian Miscellany, (1745) 555; Robert Ainsworth, Thesairis Linguae Latinae Compendiarius, (1752), 113; John Henry Grose, A Voyage to the East Indies, (1757), 274;

[3]See Tobias Smolett, The Critical Review, (1796), 406; Voltaire, The History of Candide, Translated from the French (1796), 42; Anon, "On the Three-Cornered Hat" The New-York Weekly Magazine, (Vol II, Wednesday, July 20th, 1796), 19.

[4] See, Anon, The Gentleman's Magazine, (Vol XXIII, 1753), 187; Anon, The Batchelor: Or Speculations of Jeoffry Wagstaffe, Esq, (1769). 129.

[5] Anon, A Pocket Dictionary; Or Complete English Expositor, (1758), 361.

[6] See, Anon, The British Magazine, (1746) 309. Anon, The Gentleman's Magazine, (Vol XXVI, 1756) 490, Anon, Magasin des modes noevelles, (1787) 5; Anon, "The Spectator" Harrison's British Classicks, (Vol IV, Thursday, July 26th 1786) 251.

[7]William Hickey, Memoirs, (Vol I) 140.

[8]Anon, "The Spectator" Harrison's British Classicks, (Vol IV, Thursday, July 26th 1786) 251.

[9]Anon, Magasin des modes noevelles, (1787) 5;

[10]Anon, "On the Three-Cornered Hat" The New-York Weekly Magazine, (Vol II, Wednesday, July 20th, 1796), 19.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Anon, Archives historiques et littéraires du Nord de la France (Vol III, 1833) 45. Anon, Das Ausland: Eine Wochenschrift für Kunde, (Vol 6, 1833), 965.

[2]See, Mortimer Harley, The Harleian Miscellany, (1745) 555; Robert Ainsworth, Thesairis Linguae Latinae Compendiarius, (1752), 113; John Henry Grose, A Voyage to the East Indies, (1757), 274;

[3]See Tobias Smolett, The Critical Review, (1796), 406; Voltaire, The History of Candide, Translated from the French (1796), 42; Anon, "On the Three-Cornered Hat" The New-York Weekly Magazine, (Vol II, Wednesday, July 20th, 1796), 19.

[4] See, Anon, The Gentleman's Magazine, (Vol XXIII, 1753), 187; Anon, The Batchelor: Or Speculations of Jeoffry Wagstaffe, Esq, (1769). 129.

[5] Anon, A Pocket Dictionary; Or Complete English Expositor, (1758), 361.

[6] See, Anon, The British Magazine, (1746) 309. Anon, The Gentleman's Magazine, (Vol XXVI, 1756) 490, Anon, Magasin des modes noevelles, (1787) 5; Anon, "The Spectator" Harrison's British Classicks, (Vol IV, Thursday, July 26th 1786) 251.

[7]William Hickey, Memoirs, (Vol I) 140.

[8]Anon, "The Spectator" Harrison's British Classicks, (Vol IV, Thursday, July 26th 1786) 251.

[9]Anon, Magasin des modes noevelles, (1787) 5;

[10]Anon, "On the Three-Cornered Hat" The New-York Weekly Magazine, (Vol II, Wednesday, July 20th, 1796), 19.