|

| Reenactors portraying Austrian Cuirassiers at Terezin in 2011 |

Dear Reader,

There is a narrative that touches all levels of interest in our period. Academically, as the result of figures such as Victor Davis Hanson, this narrative asserts that western militaries, from the Greeks to the present day, have traditionally relied on infantry forces, with a brief hiccup in the middle ages.[1] In reenacting, it is a simple function of cost. How many reenactors, the fine gentlemen in the picture above excluded, can afford to maintain and feed a powerful warhorse, in addition to all of the other expenses of the hobby? Finally, in wargaming, there is a powerful belief that cavalry played a much less important role in the Kabinettskriege era than the later Napoleonic Wars. After being chased by a dragoon through the Virginia wilderness in outside Yorktown in 2014, I had to ask: are these views supportable? That is the question that bears consideration today. Let us first look at Europe, before turning to North America.

|

| A Swedish Regiment of Horse receives communion after battle, by Gustav Cederstrom |

In conflicts in Europe between 1648 and 1783, cavalry played a vitally important role. Cavalry made up varying proportions of European armies in this period, from around 1/3rd (or even over 1/2!) of Swedish armies in the Great Northern War, to a much more common figure of 1/5 to 1/7 of most armies during the middle of the eighteenth century.

Even if the confines of the period forbid us from examining the cavalry of Gustav II Adolph, we can still look at the Swedish cavalry of kings Karl X Gustav, and Karl XII. For both of these monarchs, cavalry played a pivotal role in their military success at battles such as Fraustadt in 1706. Importantly, they did not view cavalry as a way to deliver firepower via the caracole (as had been common in the 1500s), but as a way to deliver a mass of mounted men towards the enemy at the trot or the canter. Charging at the gallop was not unknown, but relatively rare until the last few hundred paces before contact with the enemy.

|

| Polish Winged Hussars |

|

| Richard Knoetel's re-imagining of the Bayreuth Dragoons at Hohenfriedberg |

On the European battlefields of the mid-eighteenth century, cavalry played a decisive role time and again. Indeed, if we look at the battles of the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War, cavalry played a decisive role on numerous occasions, such as Hohenfriedberg, Rossbach, Zorndorf, Kunersdorf, Maxen, and Reichenbach. Although most useful as a weapon for chasing down a defeated enemy, cavalry could deliver smashing blows, ending a battle in their own right. Rossbach itself was a victory of Prussian cavalry almost by itself, the Prussian infantry played a secondary shaping role. At Hohenfriedberg and Kunersdorf, cavalry was able to seize upon the decisive moment, sweeping the enemy army from the field at the climax of the battle. In a lecture given at the meeting of the Seven Years' War association in 2016, Christopher Duffy suggested that a cavalry wing commander was one of the few individuals with almost absolute autonomy on an eighteenth-century battlefield.

|

| The charge of Prussian Cuirassiers at Zorndorf |

Indeed, one of the reasons for Prussia's survival and victory in the Seven Years' War was the high quality of Prussian cavalry, thanks to the reforms of Frederick II and the input of Hans Karl von Winterfeldt. Under the control of men like Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz, and Hans Joachim von Ziethen, the Prussian cavalry became a battle-winning weapon. The charge of the Bayreuth Dragoons at Hohenfriedberg certainly wormed its way into the canon of Prussian mythology. Even after Frederick the Great complained that his infantry soldiers consisted of "weakly boys" the Prussian cavalry proved its effectiveness time and again late in the Seven Years' War.

But what about warfare in North America?

|

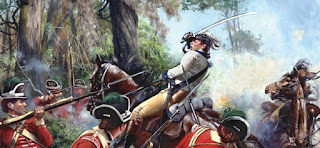

| Some Continental Dragoons run into trouble at the Battle of Eutaw Springs |

Well, first of all, cavalry obviously did not play an equally important role in North America. Among other problems, horses in North America were less readily available for military use. Aside from the Corps du Cavalry, horsemen played almost no role in the French and Indian War. Throughout the American War of Independence, cavalry forces often operated at the fringes of the larger combats, playing an important role in the war of outposts. Historian Matthew H, Spring has gone as far to suggest that the lack of cavalry played an important role in the development of quick-moving, shallow, open order tactics utilized by the British throughout the war.[3]

|

| Recreated dragoons at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse (Photo Credit: Dan Routh Photography) |

However, particularly in the southern campaign, cavalry began to take on a new-found importance towards the end of the war. Daniel Murphy has written a couple of very good posts on this subject over at The Journal of the American Revolution. Especially in the southern campaign, cavalry played an important, if not always decisive role at battles such as the Waxhaws, Blackstock's Farm, Cowpens, Guilford Court House, Hobkirk's Hill, and Eutaw Springs.

What does all this mean for historians, reenactors, and wargamers? Although large models, (such as Hanson's western way of war thesis) may be convenient to teach undergraduate courses, they need to be carefully qualified in serious study of the past. In the eighteenth century, cavalry was not simply waiting to be pushed off the stage by the advent of smokeless powder and repeating rifles: it still played a vital role in warfare.

For reenactors, using horses can be indimitating, expensive, and dangerous. I have personally been at a reenactment and witnessed horse-related injuries occur (to a person, the horse was fine.) However, having proficient mounted reenactors adds a layer of realism (not talking about the injury, here) to reenactments. There is nothing more frightening than seeing a line of horses barreling towards you.

For wargamers, taking eighteenth-century cavalry seriously is a vital step in modeling the conflict of this era. I have heard many wargamers refer to players assigned to cavalry commands as "General Kill-Cavalry," the idea being that cavalry have no purpose other than to kill one another. While such actions did indeed occur, cavalry also swept infantry from the field at Kolin, Rossbach, and Kunersdorf. I have never seen anything like the charge of the Bayreuth dragooner on the tabletop, and in most rulesets, such an occurrence would be impossible. Should spectacular equestrian phenomenon like this be allowed? Even designed for?

Although not as decisive in North America as in Europe, it is foolish to ignore the role played by cavalry during the Kabinettskriege era. Infantry may well have been the queen of battle, but cavalry played a vital role on the battlefield and certainly possessed the ability to decide the course of an action if managed correctly. This ability was recognized by competent commanders on both sides of the Atlantic, such as Friedrich II of Prussia, Leopold Joseph von Daun, Charles Cornwallis, Daniel Morgan, and Nathaniel Greene. Infantry provided stability and firepower, but cavalry gave commanders flexibility and striking power.

Feel free to share this post if you know individuals who would find it intriguing.

Thanks for Reading,

Alex Burns

[1] Hanson, Western Way of War, 9-10. For its widespread acceptance among academic military historians, see: Parker eds, The Cambridge History of Warfare, 2-3.

[2] Duffy, Military Experience in the Age of Reason, 279-80.

[3]Spring, With Zeal and With Bayonets Only, 161.